login/create account

login/create account

) Find a sufficient condition for a straight

) Find a sufficient condition for a straight  -stage graph to be rearrangeable. In particular, what about a straight uniform graph?

-stage graph to be rearrangeable. In particular, what about a straight uniform graph?  ) Let

) Let  be a simple regular ordered

be a simple regular ordered  -stage graph. Suppose that the graph

-stage graph. Suppose that the graph  is externally connected, for some

is externally connected, for some  . Then the graph

. Then the graph  is rearrangeable.

is rearrangeable. Given an integer  , an

, an  -stage graph is an

-stage graph is an  -partite graph

-partite graph  with a list of its parts

with a list of its parts  such that every edge of

such that every edge of  has endpoints in both

has endpoints in both  and

and  , for some

, for some ![$ i\in[\ell-1] $](/files/tex/87da414aab7edd9032d4b489017cd17095f73803.png) . A vertex in

. A vertex in  (

( ) is a source (target) of

) is a source (target) of  . A path in

. A path in  is plain if it goes from a source to a target through each part of

is plain if it goes from a source to a target through each part of  exactly once. The graph

exactly once. The graph  is externally connected if for every source

is externally connected if for every source  and target

and target  there exists a plain path from

there exists a plain path from  to

to  . A mask for

. A mask for  is a

is a  -stage multigraph

-stage multigraph  whose sources and targets are exactly those of

whose sources and targets are exactly those of  and such that every vertex of

and such that every vertex of  has the same degree in

has the same degree in  . The graph

. The graph  is rearrangeable if for every its mask there exists a collection, called routing, of corresponding mutually edge-disjoint plain paths in

is rearrangeable if for every its mask there exists a collection, called routing, of corresponding mutually edge-disjoint plain paths in  .

.

The graph  is ordered if each of its parts is linearly ordered. The graph

is ordered if each of its parts is linearly ordered. The graph  is uniform and denoted

is uniform and denoted  if there is an ordered 2-stage graph

if there is an ordered 2-stage graph  with equal-sized parts such that

with equal-sized parts such that  is the proper (i.e., respecting all the orders in

is the proper (i.e., respecting all the orders in  ) concatenation of

) concatenation of  identical copies of

identical copies of  . The graph

. The graph  is straight if for any

is straight if for any  and any

and any  , the number of edges joining

, the number of edges joining  with

with  equals that of

equals that of  .

.

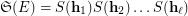

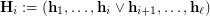

Conjecture ( ) can be reformulated as

) can be reformulated as  , where

, where  (

( ) denotes the smallest positive integer

) denotes the smallest positive integer  , or

, or  if none exists, such that the graph

if none exists, such that the graph  is rearrangeable (externally connected).

is rearrangeable (externally connected).

Examples

Consider the simple 2-regular  -stage ordered graphs

-stage ordered graphs  shown in Fig.1. It is easy to see that

shown in Fig.1. It is easy to see that  and

and  (the corresponding externally connected graphs

(the corresponding externally connected graphs  are depicted in blue). Therefore, according to Conjecture (

are depicted in blue). Therefore, according to Conjecture ( ), the graphs

), the graphs  should be rearrangeable, which is indeed the case. The graph

should be rearrangeable, which is indeed the case. The graph  is the 2-stage Shuffle-exchange graph

is the 2-stage Shuffle-exchange graph  , and there are several nice proofs known for

, and there are several nice proofs known for  . Although I am not aware of any theoretical proof for rearrangeability of

. Although I am not aware of any theoretical proof for rearrangeability of  or

or  , I have verified by brute force without difficulty that

, I have verified by brute force without difficulty that  and

and  .

.

Figure 1. Examples for Conjecture ( ).

).

Link to Beneš Conjecture

Problem ( ) and Conjecture (

) and Conjecture ( ) are equivalent "graph-theoretic" forms of Problem (

) are equivalent "graph-theoretic" forms of Problem ( ) and Beneš conjecture [B75], respectively.

) and Beneš conjecture [B75], respectively.

The equivalence is based on the natural bijection between the  -systems of partitions and the straight

-systems of partitions and the straight  -stage graphs, given any

-stage graphs, given any  . Here an

. Here an  -system of partitions is an

-system of partitions is an  -tuple

-tuple  of partitions of some finite set

of partitions of some finite set  . The image of

. The image of  under this bijection is the straight

under this bijection is the straight  -stage graph denoted

-stage graph denoted  and defined as follows. The edge set of

and defined as follows. The edge set of  is

is ![$ [\ell-1]\times E $](/files/tex/654d347529db18b97e62d7568dd0c7d15a1b02d5.png) , the

, the  th vertex part is

th vertex part is  , for all

, for all ![$ i\in[\ell] $](/files/tex/27ff80b603f9b3bd2ea80a83f7c6ab27c26475de.png) , and the edge-vertex incidence is such that every edge

, and the edge-vertex incidence is such that every edge  has endpoints

has endpoints  and

and  uniquely determined by

uniquely determined by  .

.

The bijection  provides a convenient two-way link between the frameworks for Problems (

provides a convenient two-way link between the frameworks for Problems ( ) and (

) and ( ) via numerous easily seen equivalences. Here is some basic ones:

) via numerous easily seen equivalences. Here is some basic ones:

Simplicity of

Simplicity of  is equivalent to the condition

is equivalent to the condition  , for all

, for all ![$ i\in[\ell-1] $](/files/tex/87da414aab7edd9032d4b489017cd17095f73803.png) .

.

Uniformity of

Uniformity of  is equivalent to the existence of a permutation

is equivalent to the existence of a permutation  of

of  such that

such that  , for all

, for all ![$ i\in[\ell-1] $](/files/tex/87da414aab7edd9032d4b489017cd17095f73803.png) .

.

-quasi-regularity of

-quasi-regularity of  is equivalent to every block of

is equivalent to every block of  being of size

being of size  , for all

, for all ![$ i\in[\ell] $](/files/tex/27ff80b603f9b3bd2ea80a83f7c6ab27c26475de.png) . Here the graph

. Here the graph  is

is  -quasi-regular if the induced bipartite subgraph on

-quasi-regular if the induced bipartite subgraph on  is

is  -regular, for all

-regular, for all ![$ i\in[\ell-1] $](/files/tex/87da414aab7edd9032d4b489017cd17095f73803.png) . Note that a quasi-regular multistage graph is straight. Also,

. Note that a quasi-regular multistage graph is straight. Also,  -quasi-regularity of

-quasi-regularity of  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  -regularity of

-regularity of  .

.

External connectivity of

External connectivity of  is equivalent to transitivity of

is equivalent to transitivity of  .

.

Given a permutation

Given a permutation  of

of  , the membership

, the membership  is equivalent to routability of the mask

is equivalent to routability of the mask  for

for  defined as follows. The edge set of

defined as follows. The edge set of  is

is  and the edge-vertex incidence is such that every edge

and the edge-vertex incidence is such that every edge  has endpoints

has endpoints  and

and  uniquely determined by

uniquely determined by  . Note that given

. Note that given  , the map

, the map  is surjective (but generally not injective).

is surjective (but generally not injective).

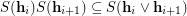

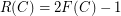

Consequently, rearrangeability of

Consequently, rearrangeability of  is equivalent to completeness of

is equivalent to completeness of  . Here

. Here  is complete if it satisfies

is complete if it satisfies  .

.

If

If  is rearrangeable, then any routing algorithm for

is rearrangeable, then any routing algorithm for  easily translates to a factorization algorithm of the same complexity for the latter identity, and vise versa. Here, given a rearrangeable multistage graph, a routing algorithm is one that takes a mask of the graph as input and returns a corresponding routing.

easily translates to a factorization algorithm of the same complexity for the latter identity, and vise versa. Here, given a rearrangeable multistage graph, a routing algorithm is one that takes a mask of the graph as input and returns a corresponding routing.

Contracting all edges between

Contracting all edges between  and

and  in

in  is equivalent to replacing the partitions

is equivalent to replacing the partitions  and

and  in

in  with their supremum

with their supremum  , given any fixed

, given any fixed ![$ i\in[\ell-1] $](/files/tex/87da414aab7edd9032d4b489017cd17095f73803.png) . In other words,

. In other words,  , where

, where  is the contracted graph and

is the contracted graph and  . In fact, the procedure

. In fact, the procedure  preserves completeness of

preserves completeness of  , as

, as  . Equivalently, the procedure

. Equivalently, the procedure  preserves rearrangeability of

preserves rearrangeability of  .

.

Counterexamples

Although the presented graph-theoretic statement ( ) of Problem (

) of Problem ( ) may look more complex, it provides somewhat more intuitive framework to study the problem and, in particular, Beneš conjecture. To illustrate this, let us now reconsider in terms of this framework and in more detail the 3 counterexamples for some extensions of Beneš conjecture discussed here.

) may look more complex, it provides somewhat more intuitive framework to study the problem and, in particular, Beneš conjecture. To illustrate this, let us now reconsider in terms of this framework and in more detail the 3 counterexamples for some extensions of Beneš conjecture discussed here.

Counterexample 1. The condition of simplicity of the graph  (essentially missing in the original statement [B75] of Beneš conjecture) is necessary for Conjecture (

(essentially missing in the original statement [B75] of Beneš conjecture) is necessary for Conjecture ( ). To see this, consider the following 2-stage 3-regular non-simple ordered graph

). To see this, consider the following 2-stage 3-regular non-simple ordered graph  :

:

Whereas  is obviously externally connected, the graph

is obviously externally connected, the graph  is not rearrageable. This is because it is evidently impossible to connect the two red vertices in

is not rearrageable. This is because it is evidently impossible to connect the two red vertices in  (a source and a target) with 3 mutually edge-disjoint plain paths.

(a source and a target) with 3 mutually edge-disjoint plain paths.

Counterexample 2. Conjecture ( ) is not directly generalizable to non-uniform graphs. More precisely, the condition of uniformity of

) is not directly generalizable to non-uniform graphs. More precisely, the condition of uniformity of  is necessary for the following reformulation of (

is necessary for the following reformulation of ( ):

):

be a simple quasi-regular ordered multistage graph. Suppose that

be a simple quasi-regular ordered multistage graph. Suppose that  is uniform and externally connected. Then the graph

is uniform and externally connected. Then the graph  is rearrangeable.

is rearrangeable. Here  denotes the proper concatenation of 2 identical copies of

denotes the proper concatenation of 2 identical copies of  . To see the necessity, consider the following simple 4-stage 2-quasi-regular non-uniform ordered graph

. To see the necessity, consider the following simple 4-stage 2-quasi-regular non-uniform ordered graph  :

:

Whereas  is obviously externally connected, the graph

is obviously externally connected, the graph  is not rearrangeable. To see this, recall that contracting all edges between two consecutive parts in a straight multistage graph preserves its rearrangeability. Therefore, if

is not rearrangeable. To see this, recall that contracting all edges between two consecutive parts in a straight multistage graph preserves its rearrangeability. Therefore, if  were rearrangeable then so would be the 3-stage graph

were rearrangeable then so would be the 3-stage graph  obtained from

obtained from  by contracting all edges in the shadowed areas. However, this is not true as it is evidently impossible to connect the two red vertices in

by contracting all edges in the shadowed areas. However, this is not true as it is evidently impossible to connect the two red vertices in  (a source and a target) with 4 mutually edge-disjoint plain paths.

(a source and a target) with 4 mutually edge-disjoint plain paths.

Counterexample 3. The stronger version of Conjecture ( ) (proposed essentially in the same paper [B75]), claiming that

) (proposed essentially in the same paper [B75]), claiming that  , is false. The graph

, is false. The graph  shown in Fig.1 is a counterexample as

shown in Fig.1 is a counterexample as  .

.

More information on Problem ( ) and Conjecture (

) and Conjecture ( ) can be found here (via Problem (

) can be found here (via Problem ( ) and Beneš conjecture).

) and Beneš conjecture).

Bibliography

*[B75] V.E. Beneš, Proving the rearrangeability of connecting networks by group calculation, Bell Syst. Tech. J. 54 (1975), 421-434.

* indicates original appearance(s) of problem.

Drupal

Drupal CSI of Charles University

CSI of Charles University